The Mystery Of How Cats Domesticated Their Human Captors

Unlike other animals, it was very likely cats that domesticated humans - not the other way round. Here's a rundown of how they managed that.

You’ll often hear pet owners say that there are two types of people in this world. There are dog people, and there are cat people. This isn’t entirely surprising.

Why should it be? Cats have an entirely different personality profile from dogs.

They’re much more wilful and independent. Whenever I’ve seen a cat interact with its human captor, I’ve always implicitly understood who wears the trousers in that relationship. But that’s not to say that cats are incapable of affection.

It’s just that cats always do things on their own terms.

As it turns out… there could be a very good reason for this.

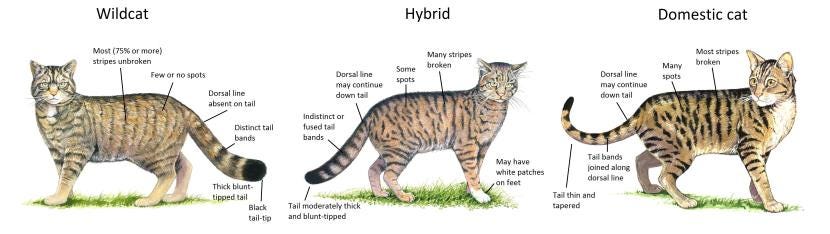

Recent genetic evidence suggests that cats weren’t domesticated by humans in the same way that dogs and livestock were. Instead, it appears that the ancestors of today’s cats set the terms of their own domestication.

It was a choice. A decision that cats took thousands of years to make.

Comprehensive studies reveal that the ancestors of today’s domesticated cats lived for thousands of years “alongside” humans before domestication. This isn’t exactly surprising. Generally, cats make for bad candidates for domestication.

Anyone who’s interacted with a wildcat knows what I’m talking about.

Cats are solitary hunters who, unlike dogs, don’t hunt in packs and lack a clear hierarchical structure that humans can take advantage of. They’re also unpredictable, making them practically impossible to train for specific tasks.

Cats are also obligate carnivores. Without meat, cats develop a taurine deficiency that eventually results in blindness and a whole host of other health problems. They’ve even lost the genes that allow them to taste sweet carbohydrates.

But while at first it may seem that this carnivorous nature would be a drawback, it could very well have been what tipped the scales in favour of domestication.

Unlike other animals domesticated by humans, this was a conscious feline decision that humans didn’t really stand to gain very much from.

It’s hard to overstate how the advent of farming changed human civilisation.

In fact, recent evidence suggests that light skin developed in Europe as an adaptation to agriculture rather than to sunlight. This is supported by evidence that gene mutations for light skin only emerged 8,000 to 10,000 years ago — coinciding not with hunter-gatherer migrations into Europe but with farming.

Moreover, lighter skin didn’t emerge in Northern Europe, but mutations for light skin first appeared in the much sunnier Anatolia (modern-day Turkey).

Another way that farming changed humanity is that it allowed us to live in settlements, as we could now grow and store grain for year-round food.

These grain stores soon attracted mice, however, which didn’t go unnoticed by cats. In fact, it’s likely that it was mouse infestations in early human settlements that provided cats with the perfect incentive to live alongside humans.

After all, where else in the wild would they get a steady supply of fresh meat?

You’ll often read the argument that it was this that led humans to keep cats around in their early settlements. However, I strongly disagree with these arguments. Ancient humans did not keep cats around to control mouse populations. That’s just ridiculous. There are just too many mice to effectively control with any number of cats. Seriously… think about it… a typical female mouse can birth anywhere between five and ten litters a year, with each litter consisting of around six baby mouse pups. Mouse populations can, therefore, theoretically, multiply by 15x to 30x over the course of a single year.

There is no way any number of cats can control this many rodents.

Ancient humans likely benefited little from keeping cats around.

What likely happened instead is that cats manipulated humans through sheer will and intelligence into tolerating them and maybe even liking them a little.

Cats don’t meow at each other. Meowing is a unique line of communication cats invented to get what they want from humans. Cats can also be insistent to the point of annoyance and will cry in an infant-like manner until they’ve conditioned their human captors to provide them with food on demand.

It took them thousands of years from venturing into the first human settlements hunting for mice through the trash to pull their con, but it really seems that it was cats that domesticated us — and not the other way around.

Don’t forget to watch this week’s YouTube video all about the origins and evolution of intelligence. Hope you really enjoy it, as it’s a bit different.

References:

Fiddes IT, Lodewijk GA, Mooring M, Bosworth CM, Ewing AD, Mantalas GL, Novak AM, van den Bout A, Bishara A, Rosenkrantz JL, Lorig-Roach R, Field AR, Haeussler M, Russo L, Bhaduri A, Nowakowski TJ, Pollen AA, Dougherty ML, Nuttle X, Addor MC, Zwolinski S, Katzman S, Kriegstein A, Eichler EE, Salama SR, Jacobs FMJ, Haussler D. Human-Specific NOTCH2NL Genes Affect Notch Signaling and Cortical Neurogenesis. Cell. 2018 May 31;173(6):1356-1369.e22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.051. Epub 2018 May 31. PMID: 29856954; PMCID: PMC5986104.

NASA (2020, March 10). Slime Mold Simulations Used to Map Dark Matter Holding Universe Together. Retrieved May 28, 2024, from https://science.nasa.gov/missions/hubble/slime-mold-simulations-used-to-map-dark-matter-holding-universe-together

Tero, Atsushi & Takagi, Seiji & Saigusa, Tetsu & Ito, Kentaro & Bebber, Daniel & Fricker, Mark & Yumiki, Kenji & Kobayashi, Ryo & Nakagaki, Toshiyuki. (2010). Rules for Biologically Inspired Adaptive Network Design. Science (New York, N.Y.). 327. 439-42. 10.1126/science.1177894.

Suzuki IK, Gacquer D, Van Heurck R, Kumar D, Wojno M, Bilheu A, Herpoel A, Lambert N, Cheron J, Polleux F, Detours V, Vanderhaeghen P. Human-Specific NOTCH2NL Genes Expand Cortical Neurogenesis through Delta/Notch Regulation. Cell. 2018 May 31;173(6):1370-1384.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.067. Epub 2018 May 31. PMID: 29856955; PMCID: PMC6092419.

Zhou, Y., Song, H. & Ming, Gl. Genetics of human brain development. Nat Rev Genet 25, 26–45 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-023-00626-5

> You’ll often read the argument that it was this that led humans to keep cats around in their early settlements. However, I strongly disagree with these arguments. Ancient humans did not keep cats around to control mouse populations. That’s just ridiculous. There are just too many mice to effectively control with any number of cats. Seriously… think about it… a typical female mouse can birth anywhere between five and ten litters a year, with each litter consisting of around six baby mouse pups. Mouse populations can, therefore, theoretically, multiply by 15x to 30x over the course of a single year.

>

> There is no way any number of cats can control this many rodents.

And how many mice do cats eat per year? And what are the effects on birth rates when mice are terrified 24/7 they are being stalked by predators, and will be killed the moment they stop being terrified and casually stroll around eating grain?